Introduction

We know that case studies are effective. Research tells us that. The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science describes their value in an introduction to the Center:

CASE STUDIES have a long history in business, law, and medical education. Their use in science education, however, is relatively recent. In our 25+ years of working with the method, we have found it to be a powerful pedagogical technique for teaching science. Cases can be used not only to teach scientific concepts and content, but also process skills and critical thinking. And since many of the best cases are based on contemporary, and often contentious, science problems that students encounter in the news, the use of cases in the classroom makes science relevant.

Case studies have proven to be effective in a broad range of disciplines. The key to their success in either a face-to-face classroom or online is the interaction of students with the content and the discussion between students — in short, the Community of Inquiry Model. Case studies – especially case studies that don’t have one clear answer or resolution – require discussion.

In a previous article, we looked at the value of interactive case studies. https://lodestarlearn.wordpress.com/2017/11/14/the-research-behind-learning-interactions/

The article elicited numerous responses from online instructors who now aspire to develop case studies for their own disciplines. The article you are now reading provides a practical guide to getting started. In this article, we particularly emphasize the story-telling aspect of case studies. Developing a good case study is indeed much like story-telling.

Case studies are an important strategy you can use to help students apply what they are learning and make them think. Using the case study strategy may be daunting for some instructors. Effectively using this strategy is a challenge. What should you think about when creating a case study? What are the options?

Generally, effective case studies are:

- Realistic

- Focused on student outcomes

- Involve the student in a story

- Involve the student in selecting and recalling information, analyzing and making decisions

Case Studies are not PowerPoints in a modified format. They are not just another means of presenting content. Students summon information when they need it. In a case study, content is only useful insofar as it can be applied to the situation at hand. Truly engaging students in the story is a challenge. Engagement means that the student summons resources, recalls information, and makes decisions. You need just enough detail to make the case study realistic but not sacrifice the learning outcomes for realism. You are a busy instructor. You don’t need a lot of production to pull this off. With that in mind, let’s get started.

Getting Started

Establish goals

This may seem like the most laborious part of the case study design, but it is necessary.

Imagine for a moment that you developed a case study for nursing students studying infectious disease control. In a case involving infectious disease control, with an outcome related to sanitation policy, you wouldn’t present symptoms to the nursing student and ask for identification of the disease. Depending on the level of the nurse, however, you might involve the nurse in decision-making related to creating and implementing a sanitation policy or reducing the risk of other patients being infected. Be clear on the outcomes. The outcome should be stated with audience, behavior, context and degree (ABCD). An example outcome: Given a Nepah virus outbreak in a small hospital, the infection nursing student will select the appropriate sanitation procedure with 100% accuracy. Think of the outcomes, objectives or competencies as the driver of the case study. They drive the presentation of content and the interactions of the learner. If it isn’t relevant to the outcome, it doesn’t belong. Parsimony is essential – meaning that a case study is economical about what is left in the case narrative and deliberate about what is left out.

For a simple case study, a paragraph or two should suffice. In more detailed cases, a page or two will be adequate. In the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, the 700 plus cases represent the range: from very short descriptions to a couple of pages presented in either narrative or dialog style. The interactive (fully online) case study can be crafted to introduce information either at the beginning of the case or as the learner engages with the case. Information can be revealed just-in-time or revealed through resources that appear as the case develops. There is no one right way or one authority. Do what comes naturally to you and won’t overwhelm the student. Experiment. Ask for student feedback.

In a case on organizational leadership, the narrative described a new CEO whose company had a top performing salesman who constantly cut corners on company procedures and angered service personnel, engineers and other sales staff. The narrative provided just enough information for the reader to fully appreciate the dilemma. Should the CEO fire or retain the salesman? Students participating in the case study were placed in the shoes of the CEO and had to draw from the content of the course to support their decision. In this case, the narrative was approximately 500 words.

Set student expectations

Make known to the student that this is a black and white case versus a nuanced case with no one right answer or visa versa. If cases are a simplified version of reality, students should know that the case study is a stepping stone to more complex cases. Avoid disillusioning students by under-preparing them for reality. If it is a stepping stone case, present it as such.

Cases can be simple with straight-forward answers or they can be complex with no clear right answer. The latter almost always requires discussion whether in class or online. As important as the solution may be the exposed thinking that leads to a solution. As important as the solution may be the sharing of student perspectives related to the solution. In either case, simple or complex, students should know what to expect. If they are asked to make a decision, for example, they need to know whether their answer will be judged right or wrong or be evaluated in a different way. Perhaps any answer is the right answer, provided that it is supported by the details of the case and the body of knowledge that pertains to the case.

In the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science site, faculty at Purdue University describe their case studies related to using statistics in science in the following way:

This set of mini cases on the ecology of eastern cottontail rabbits is designed to give students practical experience using statistics in a scientific context. Given a dataset and experimental design, groups of students are asked to play the part of a wildlife management researcher to determine the results for each study. Students practice the scientific process and gain experience making hypotheses and predictions, choosing an appropriate statistical test, interpreting and displaying results, and presenting data to others. Students choose between four basic, commonly used, statistical tests (t-test, one-way ANOVA, linear regression, and Chi-square test), and justify their choices.

To summarize, I would emphasize that students play the role of wildlife researchers, make hypotheses and predictions, choose the appropriate statistical test and justify their choices. There might only be one appropriate answer or several correct answers. The emphasis might be on ‘getting the right answer’ or ‘justifying the answer’. Either scenario is acceptable. The case study approach allows for either possibility. Again, the desired student outcomes drive the design.

In a case that involved the student in identifying risk factors related to recidivism and offenders, there was only one right answer. Either the student picked up on the risk factors, correctly categorized them, or not. In a case that involved assessing an adult student for prior learning matched to university programs, there were many possible answers. The emphasis on the latter was on following a checklist, consulting the appropriate resources and identifying the opportunities for the adult student.

Create active participants

In case studies, students should make decisions and/or perform an analysis, and contrast their work with that of others. In short, make the participants think. So much online learning contributes to a passive learning experience. Case studies should require students to recall the appropriate content and use it to make a selection or support a choice. Lengthy presentations, in which students are passive participants, are less likely to contribute to successful outcomes.

Identify what role the student is playing

Case studies may place the student in a role play. You should identify the student’s role. In one of our recent case study projects (Credit for Prior Learning), the designers placed the participants in the role of an advisor in a college setting. The advisor was tasked with recognizing prior learning worthy of college credit.

Patricia is the guide for this case study (shown in screenshot). She provides general directions on how to engage with the case before introducing the case itself.

Make it clear to the student what role s/he will play. State relevant information: job title, level of experience, etc.

I’ll refer to the Credit for Prior Learning case studies several times in this article. They were designed by the College of Individualized Studies at Metropolitan State University by Drs. Carol Lacey, Marcia Anderson, and Susan Misterek with support from Dr. Bilal Dameh and Dominic Jennen.

Identify the setting

Again, designing case studies is like telling stories. Stories are best told with settings. Be mindful that students will judge the relevance of learning based on setting and situation. Placing elementary student teachers in a college classroom setting may cause participants to dismiss the learning. They may think that ‘this doesn’t apply to me.’ On the other hand, if students recognize the setting and accept that it relates to their reality, they will judge the case study to be relevant and be open to engaging with it.

Establish the plot

Plot is a sequence of events that happen in the story that may have an impact on future events. In a case study the plot can be linear (one set of events for all students) or branched (a unique set of events for each student).

Once you have introduced the characters of the case study, the setting, and the student’s mission or objective, you need to work out the plot. As mentioned, the plot can be simple or it can be complex. In one case study that we worked on, the nursing student learned about latent tuberculosis bacterial infection. The student then observed (as a third party) the dialog between a public health nurse and a client. The student was asked to take notes during the dialog and then accurately fill out charts related to the diagnosis, treatment and outcomes. At the heart of the plot was the interview. The student couldn’t control the interview. The student simply needed to pay attention, take notes and accurately chart.

In another case study, the student played the part of an instructor asked to design an online course. The dean in the story asks the instructor about what s/he would do first, then second, then third and so forth. The story was linear (not multi-branched), but it was revealed in stages.

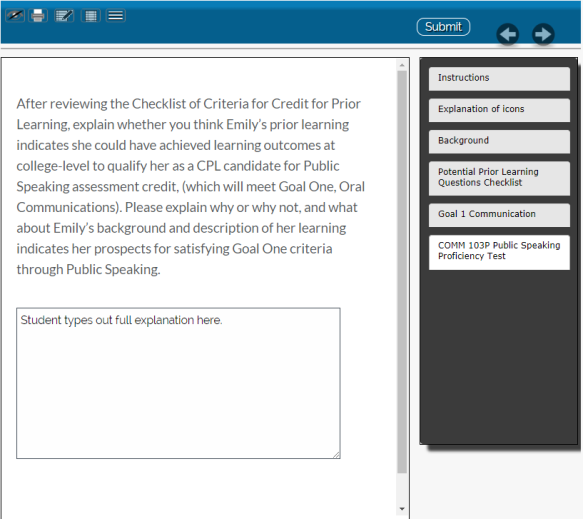

In the Credit for Prior Learning case study, the student played the part of a college faculty member who was tasked with assessing whether or not a character could earn credit for his prior learning and experience. This was a very simple plot. Information was presented on the screen and then ‘resources’ displayed. The participant could consult the resources to help evaluate whether or not the character was a candidate for prior learning. One of the resources was a checklist with key considerations: for example, was the experience related to the character’s goals? If the goal was to achieve credit for upper division courses, did the participant find any evidence of learning that was equivalent to an upper division course that contributed to the character’s goals. Simple setting and situation. Not much plot. The participant picked the right resources, consulted them and then wrote up a summary of why the character was good candidate.

Screenshot of a case study about a student who has had prior learning experience as a corporate trainer. The case study places learners in the role of an advisor who collects information and decides if the corporate trainer has had enough public speaking to meet a general education/liberal studies goal.

All three of the examples above were simple plots. But plots can be complex. Remember the ‘Choose your own adventure’ books? Rather than reading a book from cover to cover, the reader of a ‘Choose your own adventure’ makes decisions. The decision then refers the reader to another part of the book. The reader might jump from page 10 to page 20 or from page 10 to page 16. Each reader picked their own path through the narrative. The sequence of events was unique to each reader. The interactive case study can optionally branch students to different parts of the case study.

In a law enforcement case study, a parole officer interviews a client (the offender). For each page of the story, the person playing the role of a parole officer decides on one of three questions to ask the offender. The choice of question may start to move the client toward a negative emotional response. The parole officer, however, can recover from an escalating situation through a series of correct choices. On the other hand, too many incorrect choices terminates the session.

The situation and the immediate feedback immerse the student in the content. Successful case studies require students to recall lecture and reading material, select the appropriate information and use it correctly.

Avoid Combinatorial Explosions

In his book titled “E-Learning by Design” William Horton cautions against combinatorial explosions when designing games. The same wisdom holds true with complex case studies with multiple branches. Two paths can lead to four paths can lead to sixteen… Horton outlines a couple of solutions to the problem of combinatorial explosion. In one solution, which Horton calls the short-leash strategy, learners are not allowed to stray too far from the ideal path. In the above example related to the parole officer, too many bad choices terminates the session. The case study doesn’t keep on branching.

Provide Resources

Case studies are a simplification of reality. In some of our designs, we exposed resources at the appropriate time in the sequence of events. Case studies that send students off into the web or into the depths of a textbook run the risk of losing the students’ attention. Developers of case studies can make resources appear at certain times in the form of buttons or pop-ups. In the Credit for Prior Learning case study, participants clicked on a button and viewed a transcript that they had to analyze for critical information. Hyperlinks in the case study can cause pop-ups to appear with useful information.

Case Study reveals resources (buttons on right) when the student needs them. In this case, students can consult the instructions, an explanation of icons used, background of the character, a checklist, a description of a general education goal and a proficiency test.

Use Some Form of Storyboarding

Storyboard your ideas – although, the thought of storyboarding may seem daunting. It implies the use of specialized software or a specialized skill. Neither is needed.

Use pencil and paper, if nothing else. Place each scene in a box with stick figures. Outline the information that will be presented and the choices offered to the student. If your case study uses branching, draw lines between the boxes to show the branches.

In our last interactive case study, our instructional designer created a table in Microsoft Word. The table included information presented to the student, choices, feedback, and a listing of the resources that would be displayed to the student at that scene. Microsoft Word includes SmartArt. The Horizontal Hierarchy Smart Art, for example, might be useful for mapping out a case study.

Whether using pencil and paper or Word, you will find that it is easier to make changes and avoid confusion than to draft your ideas within an authoring tool. Overly complicated case studies become apparent when mapped out in advance. Most authoring tools don’t offer a birds-eye view.

Support Discussion

In simple case studies, students can make a decision by clicking on options or they can perform an analysis with text entry or drop box submission. Once students commit their answers, the case can reveal the expert answer. In more sophisticated cases, multiple answers or solutions or analyses might be appropriate. The case can step the learner through making a decision or preparing an analysis that can be submitted to a drop box or entered into a discussion post. In both simple and complex cases, the case can prepare students for an in-depth discussion about the critical aspects of their case and the rationale behind their decisions or analyses. In a flipped classroom approach, the case can engage the students online and leave precious classroom time for moderated discussion.

Vary Complexity

Cover a topic with a simple case, followed by a more complex case. In our Credit for Prior Learning course, we started with black and white cases. There was one right answer. Either the character in the case was a candidate for credit for prior learning or not. In the succeeding cases, the decisions were not so clear cut.

A strategy in game design is to start simple, ratchet up the challenge, plateau for a while, then ratchet up again. This careful control of complexity applies to case study design. Get students acquainted with the interactive case, instill some confidence and then work in the nuances and complexities of reality. Not every case study needs to be same level of complexity. Especially when designing a sequence of cases, control complexity carefully and strategically.

Conclusion

Creating case studies is story telling. They include character development, setting, plot, role play, dialog, and even suspense. They place learners at the center of the story. Unlike stories, they provide feedback – both immediate and in discussions. They are a teaching tool and they help students apply what they have learned. They are an important strategy in helping instructors making learning active. The best way to get started with case studies is to get started. There is no one model that dictates case study design. If you are making students think about your content material, you are doing the right thing.