Introduction

The complaint against eLearning is all too common: eLearning applications are boring page turners. The implication is that students flip through the material, learn enough to pass the exam and move on. The experience is transactional; not transformational. No behavioral change. No cognitive change.

Interactive case studies are one strategy to remedy the problem – but, frankly, they are a bit of a challenge to create. In past articles, I’ve introduced some of the research that supports the use of case studies. I also introduced interactive fiction as a way of getting started. If you haven’t read those posts, I’ll introduce a new example in this article and then move on to ‘first steps’.

Interactive Case Studies aren’t a recent tech fad. The example that I cite in this post dates back to 2006, but it is as relevant today as it was then. The strategy stands the test of time. More importantly, the ‘interactive’ nature of the case study is easy to reproduce technically. I chose this example because it demonstrates that even the simplest approaches can be effective.

The example is taken from case studies that were created in the Department of Rheumatology, School of Medicine, University of Birmingham. 30 interactive case studies were created all together. The following is a description of one of them. There are several critical points that are illustrated by this example. Hopefully, they will motivate you to take the first steps in creating your own case study.

Background

The authors developed an interactive learning tool for teaching rheumatology. Their reason for doing so is best explained in their own words:

“The existing medical curriculum requires that medical students have a large factual knowledge base, and as such teaching has traditionally been through lectures and rote memorization paying little attention to nurturing key problem-solving skills.

The existing medical curriculum requires that medical students have a large factual knowledge base, and as such teaching has traditionally been through lectures and rote memorization paying little attention to nurturing key problem-solving skills.

Problem solving and decision analysis are essential skills for medical students and practitioners alike. The existing medical curriculum requires that medical students have a large factual knowledge base, and as such teaching has traditionally been through lectures and rote memorization paying little attention to nurturing key problem-solving skills.” 1

1. S. Wilson J. E. Goodall G. Ambrosini D. M. Carruthers H. Chan S. G. Ong C. Gordon S. P. Young

Rheumatology, Volume 45, Issue 9, 1 September 2006, Pages 1158–1161, https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kel077

Description of case studies

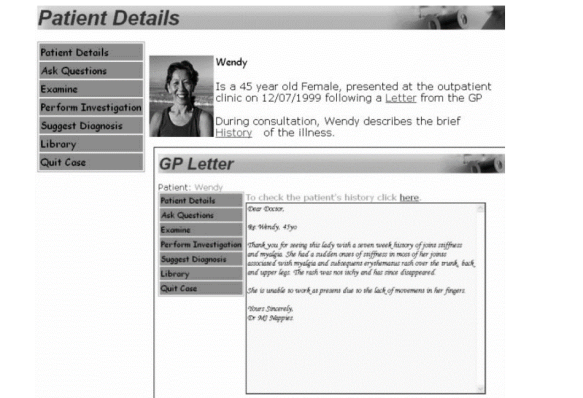

The rheumatology cases are short, reducing the burden on both authors and students. In the graphical user interface, button clicks bring up resources.

The skill required to place buttons or hyperlinks on a web page is minimal. Many authoring tools (Adobe Captivate, Articulate Storyline, and LodeStar) provide the ability to connect pages through button clicks or links. Alternatively, you can partner with your computer science, technical communications or web design department and request a student who knows HTML and is comfortable with some basic JavaScript coding. (JavaScript is a popular scripting language that is commonly taught in schools.)

In the rheumatology case studies, buttons link to a physician letter, or a library that provides a range of background information.

As pictured in the screenshot above, students can request patient details, ask questions, examine the patient, order tests and so forth. In thinking about how you might replicate this in your own course, you should know that this is relatively simple to produce. Patient details can be listed on a web page, contributing to the complete picture the student needs in order to make a diagnosis.

In the case study, the student navigates through a series of screens, each providing critical clinical information.

The user can order tests, but they come with a ‘real-world’ consequence: a financial cost is incurred that gets tallied by the program. This type of thing requires some simple JavaScript coding. The costs are assigned to a variable that is shared by all pages. If you wish to avoid that technical hurdle, you can state the cost of a test and still make an impact on the learner.

After the student collects information on the patient, s/he makes a diagnosis and prescribes treatment. After completing the case study, the student is provided with feedback and a tally of the expenditures.

Formative Assessment

Students also take an assessment in the form of multiple-choice questions that test their knowledge about rheumatology. The student can repeat components that match missed test items.

Summative Assessment

Undergraduate students were asked to produce a written report based on one of the clinical cases.

“As part of this assessment the students were expected to:

Apply their investigative skills to diagnose a range of clinical rheumatological conditions.

Explain the use of a range of clinical and scientific investigations that are required to make a successful diagnosis.

Reports were marked by two independent rheumatologists according to the reporting of the approximately 30 pieces of information or actions relevant to the case, which they were able to find, and the explanation of how these were used in the diagnosis and treatment. Student marks ranged from 55 to 95% with the majority of students gaining 70% or more on their assignment reports. All students achieved both the learning outcomes, indicating the usefulness of the approach used.”

Student satisfaction

In a survey, twenty-eight undergraduate students out of thirty-one responded positively to the interactive case study. Only thirty-eight out of fifty-three graduate students found the program useful enough to use in the future. The sharp difference between undergraduate and graduate students may be attributed to access that students had to the case studies. Graduate students were restricted to one case study.

“Both groups agreed that the program was well organized and clear, the cases were of appropriate difficulty (complexity), that it was realistic and that they had learnt from it.”

Now Your turn

This and past posts have made it evident that interactive case studies can be useful. But given your time and technology constraints, how can you create your own case studies?

To get started writing interactive case studies, follow these suggestions:

- Consider patterning your first case study on what that is offered through Open Education Resources (OER). In most cases, the author has thought through the case study and has done the hard work of including just enough detail to make the case educative and realistic.

- Keep it simple. Use button clicks or hyperlinks to enable students to navigate through the case or bring up resources.

- Include an analysis activity that requires the learner to consider the ‘evidence’ of the case and offer an opinion.

- Include the ability of the learner to compare his/her analysis with that of the expert or peers.

- Use the case study to prompt discussion.

Authoring an interactive case study might be a challenge at first. It’s a bit like creative writing – crafting a story that reveals critical information at the right time. Terse, yet engaging. Focused on one important requirement: the case study must help the student achieve an outcome.

Interactive Case Studies require ingenuity, time and a little technical know-how. To help faculty and instructional designers get started, I offer a simplified method. The intent is to get students immersed in the story, drawing upon their knowledge to choose paths, make decisions, offer an analysis and share with other students.

Interactive case studies can offer lots of bells and whistles. In contrast, this is a simplified approach – more like an interactive story or a choose-your-own adventure. Our inspiration came from a finance professor at our university. We started with an Open Educational Resource titled Personal Finance by Rachel Siegel, which our finance professor selected.

An important side note: Personal Finance is now in its 3rd edition, and is available from Flatworld. Flatworld’s stated mission is: We are rewriting the rules of textbook economics to make textbooks affordable again.

Personal Finance begins with the story of Bryon and Tomika a young couple who are currently in school and plan to get married soon. Both students will earn at least $30,000 in their first jobs after graduation and will likely double their salaries in fifteen years – but they are worried about the economy and about their job prospects after graduation. They have critical decisions to make to secure their financial future.

Rachel Siegel follows the case study with questions that the young couple or a financial advisor should answer about their situation. She then proceeds to outline the macro and micro factors that affect thinking about finances.

Set a Learning Goal

Before getting to work on patterning an interactive case study on the story in the text, we need to be clear on the learning goal. You shouldn’t start any eLearning development without a clear goal in mind. You need to answer what learning outcomes the learner will achieve by engaging in the case study. Rachel Siegel’s intent was to use the case study to make a point: there are a lot of factors to consider. Our goal in the example was to use the case study to help the learner identify the macro and micro factors that affect finances. In other words, we narrowed the scope.

Find an existing case study

In an effort to keep things simple, we patterned a case study closely on the one well thought out and communicated by the author. This might help you get started. Find a case study narrative in your own field and pattern your own case study closely on that one. If it’s a good case study it will be short but feature enough detail to provide interest and a learning situation.

Case studies are found in open education resources (eBooks, PDFs, learning repositories like Merlot.org). They are also found in case study websites like:

But be careful. Case studies are usually copyrighted. Seek permission or ensure that the case study or text is offered under a Creative Commons license.

So, to recap, the first step is to set a learning goal. The second step is to find a case study that already exists in the literature or on the web that you can pattern your case study on.

The design of our interactive case study is to provide the reader with a story (closely patterned on the text) and challenge the reader to determine which factors threatened the financial health of the characters.

This is a stepping stone case. It is not a ‘putting it all together’ where there are numerous factors, no clear cut right and wrong answers, and plenty of room for interpretation. In our case study, the learner is presented with the facts; parts of the story are revealed based on learner choice; and, at the conclusion, the learner answers some objective questions, performs an analysis, submits the analysis and compares his/her submission to the ‘expert’ analysis, which is revealed. Alternatively, the end-product could have been an analysis that was submitted to a drop box or to an online discussion.

How we built it

First, we didn’t use Rachel Siegel’s story – but one closely based on it. As an easy first step, you have the option of converting an existing case study into an interactive case study or creating a derivative case study that changes some critical details to challenge the learner. If there is any doubt about the legality or the ethics of copying the intellectual property, please contact the owner of the creative work.

Once we chose our characters, we licensed images to match the characters. Alternatively, you can use Wikimedia or find images licensed under Creative Commons. I did a search at https://search.creativecommons.org/ and immediately found images of student couples that I could easily have used.

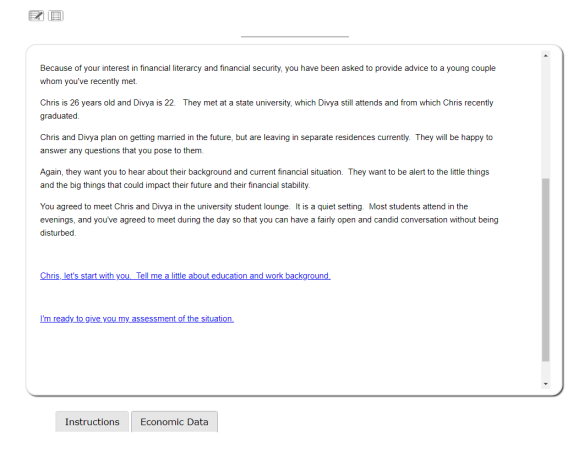

On the first page, we provided instructions. The instructions tell learners about the built-in notepad and the transcript button. These aren’t necessary. Students can take notes in any way they prefer. The transcript button shows a report of all of the feedback – but these items are more for the convenience of the learner. Traditional methods are just as effective.

Screenshot of instructions and first introduction to Chris and Divya, the characters in the case study.

Provide Choice of Paths

Put the learner in control. The characters Chris and Divya share a lot of personal financial details. The readers (learners) of the interactive story can decide what details they want to read and pay attention to. As depicted in the screen below, the reader can read details from Chris’ or Divya’s background or decide at any time to assess their situation. The reader will obviously not provide an accurate or meaningful analysis until s/he reads most or all of the facts of the case.

The essential thing here is choice. Adult learners like choice. The more complicated the case study, the more that choice matters. Given the objective, the answers to some questions will be important to pursue; others will be irrelevant.

Depending on the software that the interactive case study author chooses, choices can be presented as hyperlinks, buttons or hot spots.

If the author were using a PDF or HTML authoring tool (like Word or PowerPoint), then choices can be presented to the reader as hyperlinks. If the author were using Captivate or StoryLine, the choices can be presented as hot spots (clickable areas). In LodeStar the choices can be presented as hyperlinks or buttons.

Make Resources Available

In the case study, one of the important financial factors comes from economic data. Economic data is represented as a resource that is always available to the reader.

In the screenshot above, economic data can be accessed with a button click. The button is visible on the screen at all times.

(In some of our more evolved case studies, resources are shown only when they are needed. Some behind-the-scenes scripting allows us to show the right resources at the right time.)

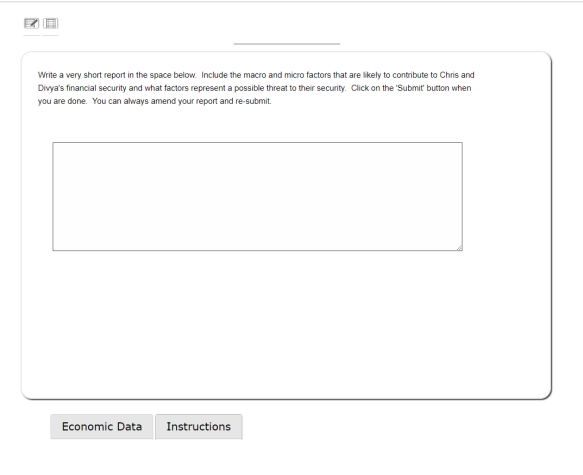

Performance and Feedback

At any point in the case study, the learner can opt to complete the assessment of the characters’ financial situation. A link to the final analysis exists on every page. It can also be presented as a permanent button on the screen. This is akin to a supermarket. The shopper can go down any aisle in any order and check out at any time when the buyer is ready.

In this case the ‘checkout’ is the final analysis. It can be presented as series of multiple choice questions (objective) or essay question or both. In our example, we chose both.

The objective items provide quick feedback. The essay item comes up after the learner clicks on ‘Complete your analysis’. The essay question reads as follows:

Write a very short report in the space below. Include the macro and micro factors that are likely to contribute to Chris and Divya’s financial security and what factors represent a possible threat to their security. Click on the ‘Submit’ button when you are done. You can always amend your report and re-submit.

The learner can consult his or her notes and base an opinion on the facts. The learner can cite the case study to support the findings. When the learner clicks on the ‘submit’ button, the expert analysis is revealed.

At our university, the student may see immediate feedback or they are asked to copy and paste their analysis into either a discussion post or into an assignment folder text field (a drop box that not only allows attachments but text entries.)

Both of these options can be supported with the same basic technical know-how used in the rest of the case study. If an eLearning authoring system like LodeStar were used, the essay submission could appear in the SCORM report of the learning management system.

Conclusion

The interactive case study presented here relies more on story-telling than it does on technical know-how. In this type of case study, the learners can choose the information that they wish to read, or ask questions that they choose to ask. In response to their decisions, information is revealed that will be used in the final analysis.

The final analysis can include objective test questions or essay items or both. In a simple low-tech situation, the learner can write the essay in Word and then submit that to a drop box or assignment folder. The interactive case study simply provides the background information and the essay prompts.

Low-tech or high-tech, the learner is asked to examine the information and consider its importance in the final analysis related to the learning outcome. The learner is being asked to ‘activate’ thinking rather than mindlessly store and retrieve content. The result is better outcomes for students.