Introduction

Case Studies are an effective teaching and learning tool. A literature review shows the efficacy of case studies in promoting active learning, problem solving, and critical thinking. But case studies vary in style. Research seldom examines the different formats of case studies and how they can impact learning. At a detailed level, there is no one prescription to how to write a case study. They should all involve analysis, thinking, decision-making, application of critical skills and discussion. But in online interactive case studies, there are multiple ways that this can be accomplished.

In some examples, long narratives are provided to students for discussion; in others, the narrative is divided into short segments and interspersed with questions and decision points that engage the learner.

An example of the long narrative is The Elusive Tuberculosis Case: The CDC and Andrew Speaker

https://casestudies.ccnmtl.columbia.edu/case/elusive/

One of the challenges presented in this case is how to manage communicable disease patients when slow diagnostic procedures mean health officials must make decisions and communicate with patients before they have complete information. An instructor would introduce the case to students and invite discussion on how to manage the problem. The interactive nature of this type of case study is in the discussion (i.e. Student to student and student to instructor interaction)

The latter example (narrative divided into short segments) is often featured in interactive student-to-content interaction. In this example, students interact with the content and then prepare for class discussion or online interaction with other students.

The latter example, however, presents a challenge to instructors. Some case studies are intended to behave like interactive narratives, but result in an experience that feels more like an assessment rather than engaging interactive story-telling. Much of the research underscores the importance of case studies as an effective teaching tool; but the style of case study has not been closely examined. Instructors may wish to choose an interactive style because of a personal preference or because of their student audience. Some instructors may wish students to think critically and therefore require students to apply their knowledge by making the right decisions. The student-to-content interactive format supports that outcome – but, in my opinion, should never be chosen in lieu of online or class discussion.

Interactive Case Studies

As I alluded to, faculty who are unaccustomed to writing interactive case studies may unwittingly create a traditional assessment rather than an interactive case study. In an assessment labelled as a case study, the instructor presents information and then checks for understanding. The presentation of content occurs at the beginning with all of the information given to the learner at once. In at least one style of case study, the learner is presented with background and setting information, but the remainder of the information unfolds in short pieces with the learner engaged in a lot of decision-making along the way. The structure of an assessment looks like this, where ‘I’ denotes information and ‘Q’ denotes a question:

I – I – I – I – Q – Q – Q

The structure of an interactive case study looks more like this:

I – I – Q – I – Q – I – Q

In other words, in the first example, the case study looks less like a story that is unfolding and involving the learner in critical decision-making and more like an online quiz. Questions and answers. The second example provides background information and setting and then engages students in decision making at many points of the narrative. The story unfolds in short pieces followed by a student interaction, such as a decision point.

Writing a case study as an unfolding story takes some practice and skill. Critical information about characters and setting may be revealed at the beginning – but more information is revealed as the learner reads passages and makes decisions.

The question of what to reveal and when is a critical skill. It is only one of several critical skills – but merits special attention. It is closely related to the art of story-telling. In short, if we can practice story-telling with instructional purpose, we will write more engaging, interactive case studies when the need arises. But how can we make use of story-telling in our courses and where are the instructional examples? In my quest, I discovered Interactive Fiction.

Interactive Fiction

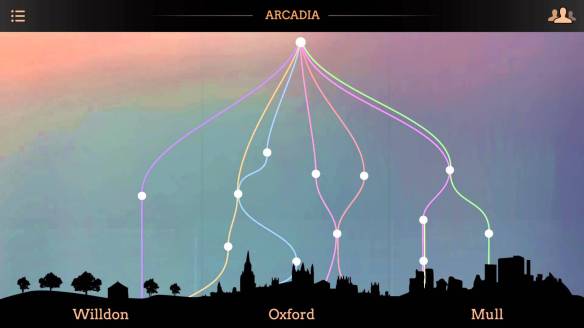

I am familiar with the old “Choose your Own Adventure” originally published by Bantam, but the digital Interactive Fiction genre is new to me. I button-hooked one of my colleagues at the university, and was given a starter list of titles to investigate. The world of Interactive Fiction was uncovered for me with three distinct forms that caught my interest. The first was very sophisticated story-telling. An example was Arcadia by Iain Pears. The author required a new technology for readers to explore a story from the points of view of multiple characters. In Arcadia, the novel follows ten separate stories that intersect at key points. The author needed a new form of interactive technology so that readers would know where they were in the narrative, see a graphical depiction of the interweaving plot lines, and be able to switch easily between characters.

In Iain Pears’ own words,

As I wanted to write something even more complex, I began to think about how to make my readers’ lives as easy as possible by bypassing the limitations of the classic linear structure. Once you do that, it becomes possible to build a multi-stranded story (10 separate ones in this case) where each narrative is complete but is enhanced when mingled with all the others; to offer readers the chance to structure the book as best suits them. To put it another way, it becomes fairly straightforward (in theory) to create a narrative that was vastly more complex than anything that could be done in an orthodox book, at the same time as making it far more simple to read.

Iain Pear

Screenshot of Arcadia app on an iPad

The second form that caught my interest was The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Readers are described a setting with objects (e.g. light, door, dressing gown). In Hitchhiker, readers start off in a dark room. They must type in text commands to turn on light, get up, get gown, wear gown, open pocket, and eventually exit the house to start the adventure.

A Screenshot of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

The third form sparked the greatest interest in me – because, with the right tools, instructors can use this form to great advantage in promoting a skill or supporting a critical learning outcome. The third form will take less time to produce than the others and doesn’t require high-tech tools.

An example of this form relates to the Japanese Internment camps of World War Two America. In this example, you are placed in the role of a young male of Japanese descent living in California during the war. Rather than simply reading a long narrative about the challenges of people of Japanese origin, you are placed in the story and required to make critical life-changing decisions. Reading any text can be an active experience when students are engaged and not skimming. Reading Interactive Fiction and making decisions is yet another strategy for engaging students and activating their thinking.

The lights came on for me with this example. This is a very simple example of Interactive Fiction, which can alternatively be described as a text adventure or even a game.

The potential of Interactive Fiction to immerse students in the content and cause them to think critically about a subject is apparent. This is a simpler version of the Decision-Making design pattern that I’ve discussed in this web journal and a simpler version of an interactive case study. It has merit on its own and it builds skills for these other types of interactions.

So let’s explore the elements of this type of Interactive Fiction or text adventure. If you were to create one for your own course, what should you do? Here are some steps to follow.

Seven Steps

- Provide background.

For example, the author of the Japanese-American Internment text adventure, introduced the story with the following narrative:

“While many people think about the internment as a situation that, by denying internees their most basic civil rights, effectively stripped them of their ability to control any aspect of their lives, this game allows you to realize that in fact the internment was all *about* decision-making. At every turn, internees were bombarded with dilemmas: whether to answer “yes” or “no” to a loyalty questionnaire; whether to join the growing resistance movement or stay quiet; whether to throw one’s lot in with one’s country or one’s race. There were rarely any satisfying answers to these questions; indeed, the very fact that internees had to answer them at all speaks to how profoundly unjust was the government’s decision to imprison them.”

TFickle — author of Japanese-American Internment Text Adventure

- Design the Interactive Fiction to be played many times, which offer the reader the value of different experiences or perspectives.

- Base the story on fact or the concepts and principles that lie at the core of this educational experience:

The author of Japanese-American internment wrote this:

For the content and characters of the game, I’ve drawn on a broad range of historical and literary sources, especially the Supreme Court case of Fred Korematsu, and John Okada’s novel “No-No Boy.” In fact, nearly all of the situations which you will face are ones which have actually happened.

- Choose characters, and thus, different points of view and different experiences. Interactive Fiction allows students to view the experience from the points of view of different characters. Interactive Fiction thrives on this concept. Regional conflict can be viewed from the points of view of characters belonging to each of the warring factions, for example.

- Provide a short description of setting and character. Keep it to the point without requiring too much reading.

- Organize the Interactive Fiction so that students don’t have to read a long passage before being engaged in making a decision. Keep the students actively engaged.

- Use convergence or a short leash strategy (explained later).

In my first try at Japanese Internment, I answered a loyalty questionnaire almost immediately into the story; in another try, I tried to avoid internment by submitting to facial surgery. The facial surgery didn’t help. I eventually ended up in jail and needing to answer the loyalty questionnaire. In other words, my surgery path and choices eventually converged into the original path that I took on my first try. Managing the ‘combinatorial explosion’ (as William Horton describes it in ‘E-Learning by Design’) is an important strategy for avoiding branches leading to more branches leading to more branches… The increase in branches becomes exponential. A short leash strategy means that readers can stray from the main path, but are eventually led back.

In interacting with the Japanese Internment situation, I realized that even after the horror of denouncing your heritage and being imprisoned anyway, you live through the aftermath of the war and the scorn visited upon you for your decisions. By this point I was in the skin of the Japanese boy. As a result of short narratives and decision-making, I became part of the story.

Conclusion

Interactive Fiction or interactive story telling is great preparation for interactive case study writing. An Interactive Case Study is a combination of interactive fiction and decision-making scenario. My interest in Interactive Fiction started with the problem of how can we develop the art and skills of interactive story telling in faculty who want to create interactive, engaging case studies. But on my journey, I saw examples that highly recommend Interactive Fiction as a strategy in and of itself. A history faculty member could take one event from the American Civil War and write the experience from the points of view of both a confederate and union soldier. An Information Systems instructor can investigate requirements gathering from the point of view of the customer and the analyst. These are short pieces that may perhaps replace a straight-forward narrative and increase the engagement of students.